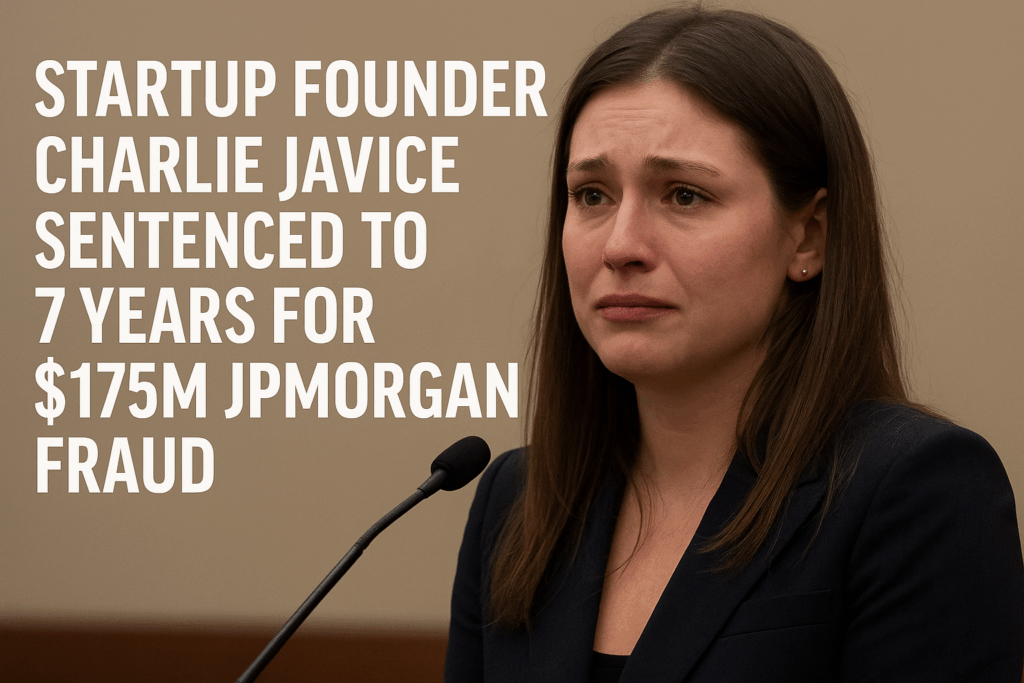

A once-celebrated fintech prodigy, Charlie Javice, was sentenced Monday to seven years and one month (85 months) in federal prison for engineering a $175 million fraud that duped JPMorgan Chase into acquiring her startup, Frank.

The 33-year-old entrepreneur was convicted in March. She stood trial with her chief growth officer, Olivier Amar. The jury deliberated for less than two days before finding both guilty. They faced three counts of fraud and one count of conspiracy after exaggerating Frank’s customer base by millions. Prosecutors pressed for a 12-year sentence. U.S. District Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein handed down an 85-month term. He cited the need for deterrence but acknowledged Javice’s personal remorse.

“I will spend my entire life regretting these errors,” Javice told the court through tears as she apologized to JPMorgan, her employees, and her family. “I’m asking with all of my heart for forgiveness … I will accept your judgment with dignity and humility.” Turning to relatives seated in the front row, she thanked them for their “unwavering support.”

Hellerstein described her remarks as “very moving” and praised her previous life of service. He said contrition alone could not excuse her conduct. “I sentence people not because they’re bad, but because they do bad things,” the judge said. “I don’t think you’ll be committing other crimes and that you’ll be devoting your life to service. But others have to be deterred.” Javice was ordered to forfeit $22.36 million and pay $287 million in restitution to JPMorgan. She will serve three years of supervised release, in addition to her prison term.

The sentence closes a chapter in one of the most high-profile corporate fraud cases to hit the financial sector in recent years. Javice founded Frank in 2017. She stated its mission was to streamline the federal student aid application process. By 2021, the platform had gained attention from investors and mainstream media. JPMorgan seized on the opportunity to expand its reach into the student market. When the acquisition was announced, the bank stated that Frank had served over five million students.

But those numbers quickly unraveled. Within months, JPMorgan discovered the startup had fewer than 300,000 legitimate users. The rest were fabricated to inflate its appeal. Testimony at trial revealed that Javice directed employees to generate fake records in the days leading up to the sale. One staffer recalled resisting her instructions. Javice responded, “Don’t worry. I don’t want to end up in an orange jumpsuit.”

Her defense argued that, unlike other frauds, Frank offered a real product that helped students. Attorney Ronald Sullivan compared her to Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes, who received 135 months in prison for deceiving investors about nonfunctional technology. “Ms. Javice’s sentence should be nowhere near Elizabeth Holmes’,” Sullivan said.

Prosecutors disagreed, contending that the scheme was fueled by greed and designed to secure a $29 million personal payout for Javice. Assistant U.S. Attorney Micah Fergenson summed up their position bluntly: “JPMorgan didn’t get a functioning business; they acquired a crime scene.”

The scandal has also proven embarrassing for JPMorgan, which is long considered among the most sophisticated corporate acquirers. The bank had been on a buying spree in fintech. It aimed to outpace rivals and stave off competition from big tech firms. Yet in its haste, JPMorgan failed to verify Frank’s reported user base before striking the $175 million deal.

Though Javice remains free on bail pending appeal, the sentence marks a reckoning for startup founders and investors. The case joins other stories of entrepreneurs whose exaggerations ended in court and prison.