A crushed skull unearthed on a riverbank in central China more than three decades ago has been digitally reconstructed — and its features are forcing scientists to reconsider when and where modern humans emerged.

Researchers reporting Thursday in Science said the fossil, known as Yunxian 2, belonged not to Homo erectus (an extinct species of early human), as previously assumed, but to a lineage that includes the mysterious Denisovans (an extinct group of archaic humans identified mainly by genetic evidence) and the recently named “Dragon Man” (Homo longi, a proposed extinct human species). If correct, the finding would push the origins of Homo sapiens back by nearly 400,000 years, recasting long-held assumptions about human ancestry.

“By one million years ago, our ancestors had already split into distinct groups, indicating a much earlier and more complex evolutionary split than previously believed,” said study coauthor Chris Stringer, paleoanthropologist at London’s Natural History Museum.

The analysis places Denisovans—a population known almost exclusively from genetic traces (such as DNA found in ancient bones)—closer to modern humans than to Neanderthals (another extinct species of archaic humans). According to the study, Homo sapiens and Denisovans may have shared a common ancestor 1.32 million years ago, while Neanderthals diverged slightly earlier, at about 1.38 million years ago. That is roughly twice as old as conventional estimates, which have generally dated the last common ancestor of these groups to between 500,000 and 700,000 years ago.

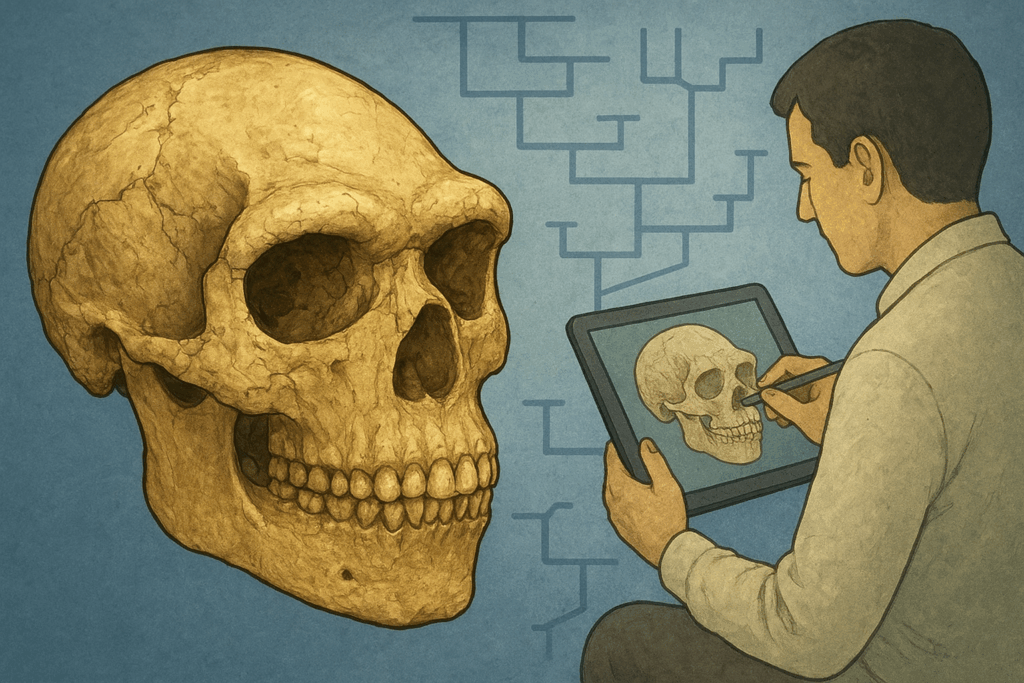

The Yunxian fossils were discovered in Hubei province in 1989 and 1990, with a third skull unearthed at the same site in 2022. Because of their poor preservation, the remains had long resisted classification. However, the new study employed CT scanning (a type of X-ray imaging that provides detailed internal images), structured light imaging (a technique that projects light patterns to capture surface shapes), and virtual modeling to digitally “undo” millennia of crushing. “There were so many cracks and broken pieces,” said Chinese Academy of Sciences researcher Xijun Ni. “It’s very much like a digital surgery.”

What emerged was a skull both familiar and strange. The braincase is squat and robust, resembling Homo erectus (an early human ancestor), but other traits—including relatively flat cheekbones and a larger brain capacity (the internal volume of the skull)—align more closely with modern humans and Homo longi. In 2021, another team formally identified Homo longi from a remarkably preserved skull found in northeastern China, nicknamed “Dragon Man.”

Some experts welcomed the technical achievement but were cautious about its evolutionary implications. “This study says that Denisovans (Homo longi—a human species proposed from fossils) and Homo sapiens are more closely related to the exclusion of Neanderthals,” said Ryan McRae, a paleoanthropologist (an expert in ancient humans) at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. “It also goes one step further, saying that the origins of all these groups are much older than expected, about twice as old if not more.” While praising the reconstruction as “fantastic,” McRae warned that the phylogenetic analysis (the study of evolutionary relationships) may have “tried to do too much at once with limited data.”

Other critics went further, pointing out that genetic studies to date support a more recent divergence (the process in evolution where species split from a common ancestor). Marta Mirazón Lahr, a Cambridge archaeology professor not involved in the work, said she remains “unconvinced by the dates suggested.” Nobel laureate Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute also cautioned that without DNA or protein evidence, “there is not enough information from the morphology (the shape and structure of fossils) of these specimens to confidently determine how they are related to each other, much less date the divergences between them.”

Despite skepticism, the reconstruction has breathed new life into a fossil that was once considered too distorted to be informative. Now, researchers hope the third Yunxian skull, discovered three years ago, will yield additional insights. As Stringer acknowledged, “Some researchers may be skeptical of these relatively deep divergence dates. But if Yunxian is indeed an early member of the longi-Denisovan clade, this necessarily pushes back the minimum age of that clade to at least 1 million years.”

The findings highlight how even fragmentary fossils can reshape our understanding of human origins. As Xiaobo Feng of Shanxi University, the study’s lead author, noted, “A fossil of this age is critical for rebuilding our family tree.” Whether Yunxian 2 becomes a pivotal chapter or a cautionary footnote, its digital reconstruction highlights both the promise and uncertainty in our quest for roots.