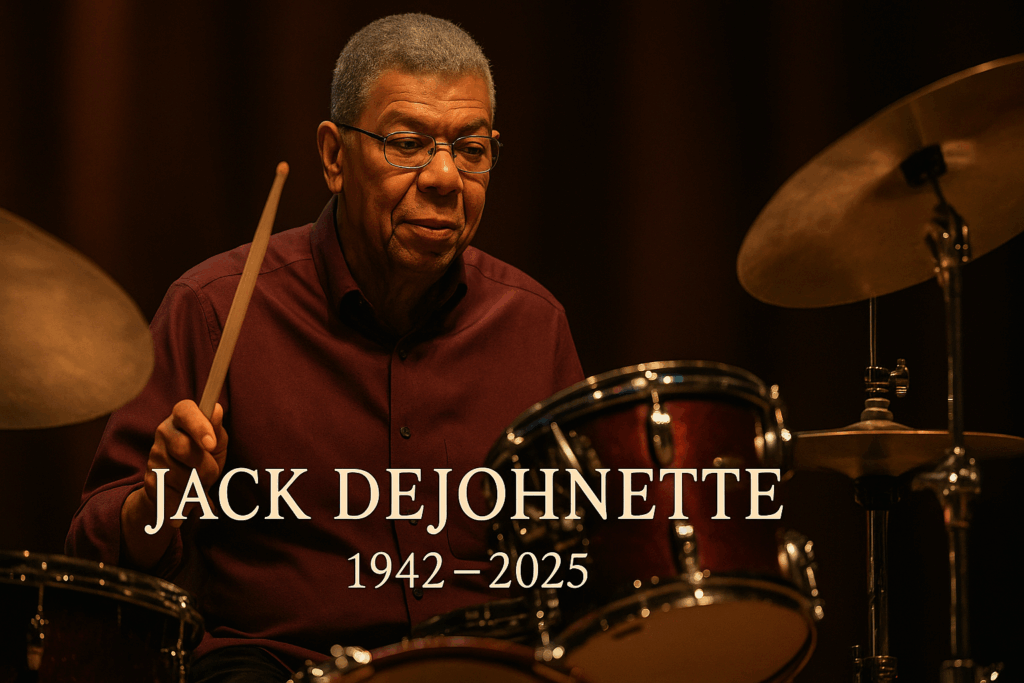

Jack DeJohnette, a revolutionary jazz drummer, pianist, and bandleader, has died at 83. His innovative touch reshaped modern jazz and bridged generations of musical styles. His family said he died Sunday of congestive heart failure at a hospital in Kingston, New York.

For more than 50 years, DeJohnette has been a defining voice in American jazz. His rhythmic command and tonal sensitivity made him indispensable to the art’s evolution. From his early years in Charles Lloyd’s quartet to his electrified collaborations with Miles Davis and his decades-long partnership with pianist Keith Jarrett, DeJohnette stood at the center of jazz’s transformation. He spanned bebop, fusion, and the avant-garde.

“I’m like a colorist on the drums,” he said in a 2015 interview, describing his approach as both painterly and elastic. “I can work within time, but I can also be free of it.”

Born in Chicago on Aug. 9, 1942, DeJohnette was the only child of Jack Sr. and Eva Jeanette DeJohnette. Raised on the city’s South Side by his grandmother, he grew up surrounded by a rich tapestry of sounds. These ranged from jazz and classical radio to country broadcasts of The Grand Ole Opry. His uncle, Roy Wood Sr., a pioneering Black radio announcer and jazz DJ, introduced him to Chicago’s clubs and legends. He even let him join in once on kazoo with blues icon T-Bone Walker.

Initially trained as a pianist, DeJohnette’s path changed when a friend left a drum kit in his basement. He began imitating his heroes—Max Roach, Art Blakey, and Vernel Fournier. He found the instrument intuitive. “It took me about a week just to get my independence on the drums,” he recalled in a Smithsonian oral history. “It somehow came naturally to me.”

By the mid-1960s, he had become a fixture in Chicago’s avant-garde circles. He performed with Sun Ra and saxophonist Eddie Harris before moving to New York in 1966. He took this step on the advice of pianist Muhal Richard Abrams of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). His break came when he joined Charles Lloyd’s quartet, which included pianist Keith Jarrett and bassist Cecil McBee. The group’s fusion of post-bop, R&B, and psychedelic rock made them a rare jazz act at major rock venues like the Fillmore and Monterey Jazz Festival.

Miles Davis soon took notice. DeJohnette joined Davis’s group in 1969. He helped propel the groundbreaking Bitches Brew sessions with his crisp, funk-driven beats and spontaneous interplay. Davis later wrote that DeJohnette “gave me a certain deep groove that I just loved to play over.” Onstage, as captured on the live album Live-Evil, his rhythmic flexibility and energy blurred the line between jazz and rock. The result was a volatile, hypnotic sound.

After leaving Davis’s band in 1971, DeJohnette formed his own groups. These included New Directions and Special Edition, where he showcased both his compositional range and the rhythmic spectrum of modern jazz. This spanned from cascading swing to free-form experimentation. The New York Times noted that his arrangements and horn voicings offered “each soloist a different sort of challenge.”

In 1983, he reunited with Jarrett and bassist Gary Peacock to form the long-running Standards Trio. It is one of the most beloved acoustic ensembles in contemporary jazz. “I think we endure because we play every piece as if it were new for the first time,” DeJohnette said near the end of the group’s three-decade run.

Over the next decades, DeJohnette continued to explore new terrain. His later works ranged from hard rock collaborations (Music for the Fifth World, 1992) to meditative soundscapes like Peace Time (2006), which earned him a Grammy Award. In 2015, he revisited his avant-garde roots on Made in Chicago and reunited with Abrams and other AACM pioneers.

DeJohnette’s influence extended to younger generations through many projects. These included his trio with saxophonist Ravi Coltrane and bassist Matthew Garrison and his Hudson quartet with John Scofield, John Medeski, and Larry Grenadier. “Jack at heart is kind of a free player,” Grenadier said in 2017. “His spirit is so free, and he’s willing to step to that edge in a heartbeat.”

DeJohnette was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2012. This is the nation’s highest jazz honor. He is survived by his wife of 57 years, Lydia DeJohnette, who also served as his manager, and their daughters, Farah and Minya.

Even late in life, DeJohnette remained reflective about his musical journey. “I think I play well enough to tell a story,” he told The Times in 2024. His story — one of boundless rhythm, freedom, and imagination — continues to echo through every corner of modern jazz.